Textiles of India at the V&A

Hits: 248919th October 2015

The V&A 's David Bowie and Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty exhibitions provided insights into the visionary genius of fashion leaders. It’s current exhibitionTextiles of India explores the origins of producing beautiful threads from the earth’s raw materials

Blues, reds, yellows and greens

India has provided the world with cotton and silk for centuries. Indian cotton was known to the Romans as “woven winds.” By the 1630’s fine quality, cheap fabrics imported from India by the Dutch and the British caused the complaint, “You can’t tell servant from master.”

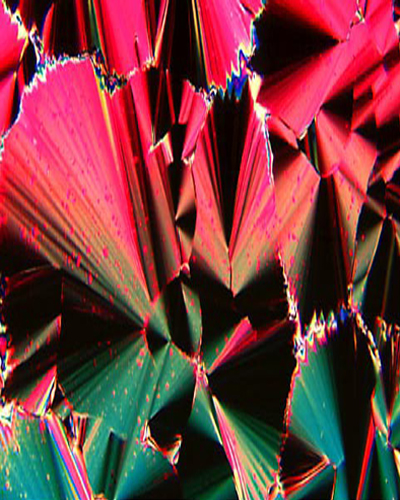

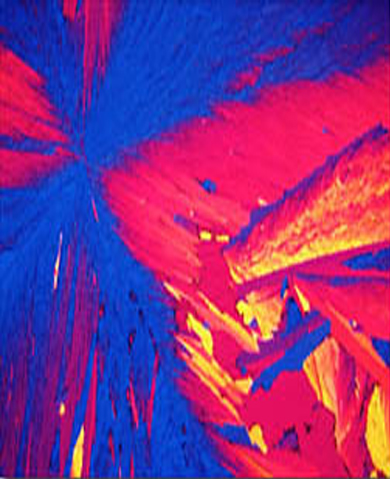

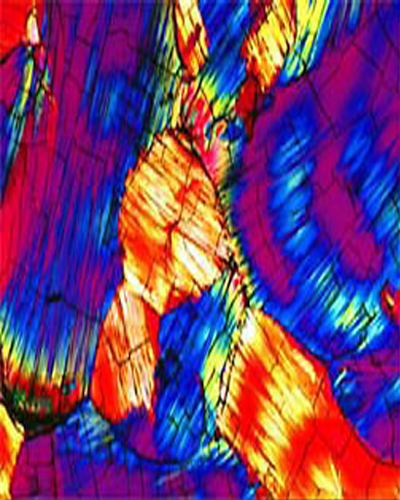

The art of extracting colour from nature begins with a nod to indigo dyeing. Indigo is the magical blue colour derived from the leaves of the plant Indigofera tinctoria. And, India’s name is inextricably linked with both indigo and Indikon, the ancient Greek word for dye. Issac Newton named the sixth colour of his prism after it in 1660 when the East India Company were importing the pigment into England. An infinite array of patterns can be produced on cloth by string or wax resist dip-dyeing.

From the deepest red to the lightest pink, the shades so indicative of India’s crazily colourful chintz, are extracts from the root bark of the chay plant (Oldenlandia umbellata) which grows around the southern tip of India and in Sri Lanka. Unlike indigo, chay requires a mordant or a fixative to bind colour with cloth. A vibrant golden orange extract of turmeric flowers, plants and roots (Curcuma longa) combines with indigo to make green. Surprisingly, pomegranate rind is rich in tannins from which numerous earthy and yellow tones come.

Cotton and silk India’s raw materials

Eri and Muga silk is made from the larvae of the Antheraea moth, native to the Assam region. The caterpillars are bred indoors and then transferred outside to munch on Mulberry trees. Once the mulberry silkworms have stripped the leaves, they are moved onto fully-leafed trees and protected from predators by their cultivators. After the fat silkworms finish feasting and have spun a hard and compact cocoon from one long continuous strand of saliva, they are harvested and sold to silk reelers by the sack load.

Women unpick the cocoons by hand and wind them onto factory spindles: the thread is so fine that several strands are spun together to make one strand of silk. It's intensive work, since around 400 cocoons are needed to make one shawl. Other insects are used to make eye catching embellishments: the wing cases of jewel beetles impart a blue, violet and green iridescence to decorative cloths.

Cotton handkerchiefs, silk neckerchiefs called choppas, bandannas and turbans from Madras and Bengal are transformed into objects of beauty by tie-dye or more intricate block printing techniques. By the 1700’s, English gentlewomen were wearing squares of Indian kerchiefs, or small shawls, as a warm extra layer of clothing.

Textiles tell stories

The Hindu rulers of the Mughal Empire drew upon local traditions to inspire religious and secular textiles to tell stories that maintained their absolute monarchy. Splendid Mughal flower and bird designs were created with Gujarati needle and hook (ari) techniques. The softer shades of peach pay homage to the natural world and inform the Victorian William Morris Arts & Crafts movement.

A processional walkway between two of the exhbition rooms is lined with endless lengths of red string casting colour like fabric laser beams. Velvet wall hangings and floor coverings shimmer with metal coated threads and gold leaf, and strips of gilded silver chevrons pattern shawls for courtly wear. A multi-armed Gangamma Goddess, she of the holy water wishing-well, dazzles from a copper panelled wall. Funerary tents and banners stitched with organic forms, similar to a modern Picasso and Matisse paper cutouts, honour the dead.

An impressive map shawl, circa 1700, depicts the winding Indus river busy with boats and numerous quieter tributaries, and the surrounding forests, townhouses and people. A whole way of life is described on a pashmina made in Kashmir with hand coloured underhair from goats and yaks.

The textiles of India exhibition demonstrates that fabrics can be produced in ways that are sympathetic to ecological, social and environmental needs without relying on polluting chemicals. It also serves as a reminder that Nature’s vibrant colours and forms are the source and inpiration for beautiful, functional and durable fabrics that become ever more beautiful with use.